#because he was 'gay coded'. since he wore a pink tie.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

asexual reigen posting going unhindered... nature is healing

#you may not believe me but headcanoning reigen as asexual would get you accused of homophobia in 2019#because he was 'gay coded'. since he wore a pink tie.#i also dont understand the logic but people were very passionate about this

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dead Fandoms, Part 3

Read Part One of Dead Fandoms here.

Read Part Two of Dead Fandoms here.

Before we continue, I want to add the usual caveat that I actually don’t want to be right about these fandoms being dead. I like enthusiasm and energy and it’s a shame to see it vanish.

Mists of Avalon

Remember that period of time of about 15 years, where absolutely everybody read this book and was obsessed with it? It could not have been bigger, and the fandom was Anne Rice huge, overlapping for several years with USENET and the early World Wide Web…but it’s since petered out.

Mists of Avalon’s popularity may be due to the most excellent case of hitting a demographic sweet spot ever. The book was a feminist retelling of the Arthurian Mythos where Morgan Le Fay is the main character, a pagan from matriarchal goddess religions who is fighting against encroaching Christianity and patriarchal forms of society coming in with it. Also, it made Lancelot bisexual and his conflict is how torn he is about his attraction to both Arthur and Guinevere.

Remember, this novel came out in 1983 – talk about being ahead of your time! If it came out today, the reaction from a certain corner would be something like “it is with a heavy heart that I inform you that tumblr is at it again.”

Man, demographically speaking, that’s called “nailing it.” It used to be one of the favorite books of the kind of person who’s bookshelf is dominated by fantasy novels about outspoken, fiery-tongued redheaded women, who dream of someday moving to Scotland, who love Enya music and Kate Bush, who sell homemade needlepoint stuff on etsy, who consider their religious beliefs neo-pagan or wicca, and who have like 15 cats, three of which are named Isis, Hypatia, and Morrigan.

This type of person is still with us, so why did this novel fade in popularity? There’s actually a single hideous reason: after her death around 2001, facts came out that Marion Zimmer Bradley abused her daughters sexually. Even when she was alive, she was known for defending and enabling a known child abuser, her husband, Walter Breen. To say people see your work differently after something like this is an understatement – especially if your identity is built around being a progressive and feminist author.

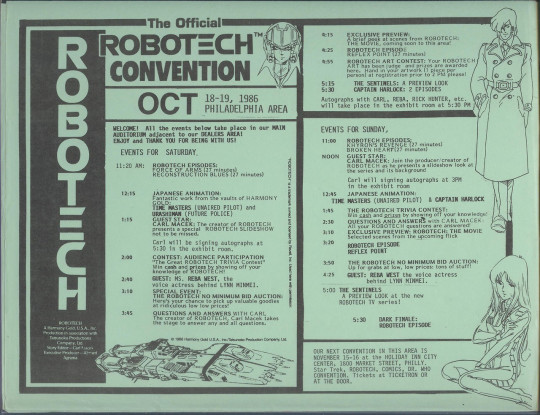

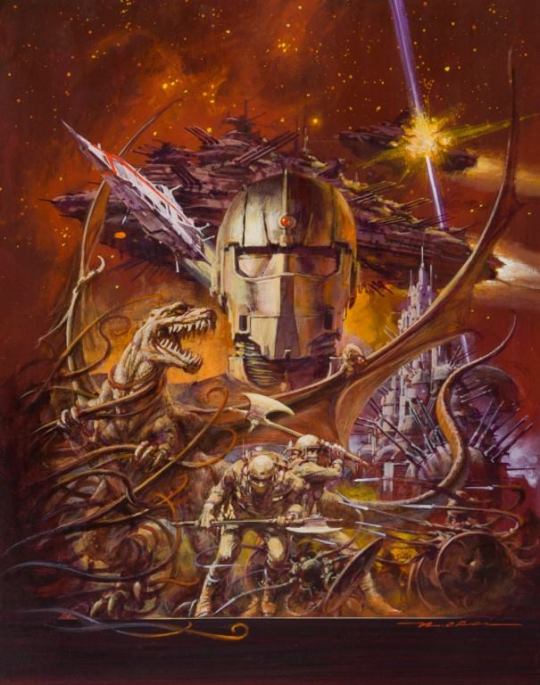

Robotech

I try to break up my sections on dead fandoms into three parts: first, I explain the property, then explain why it found a devoted audience, and finally, I explain why that fan devotion and community went away. Well, in the case of Robotech, I can do all three with a single sentence: it was the first boy pilot/giant robot Japanimation series that shot for an older, teenage audience to be widely released in the West. Robotech found an audience when it was the only true anime to be widely available, and lost it when became just another import anime show. In the days of Crunchyroll, it’s really hard to explain what made Robotech so special, because it means describing a different world.

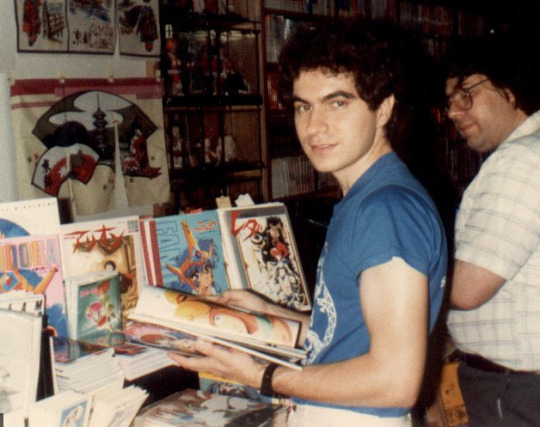

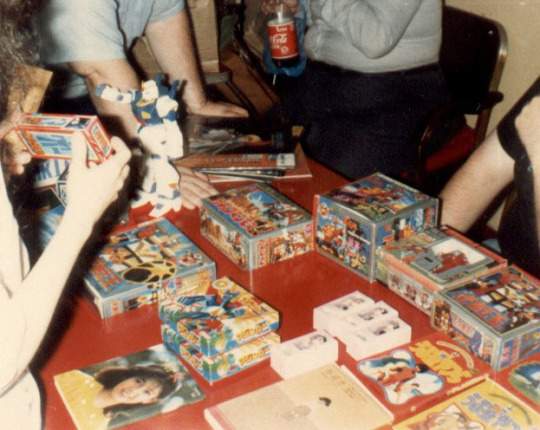

Try to imagine what it was like in 1986 for Japanime fans: there were barely any video imports, and if you wanted a series, you usually had to trade tapes at your local basement club (they were so precious they couldn’t even be sold, only traded). If you were lucky, you were given a script to translate what you were watching. Robotech though, was on every day, usually after school. You want an action figure? Well, you could buy a Robotech Valkyrie or a Minmei figure at your local corner FAO Schwartz.

However, the very strategy that led to it getting syndicated is the very reason it was later vilified by the purists who emerged when anime became a widespread cultural force: strictly speaking, there actually is no show called “Robotech.” Since Japanese shows tend to be short run, say, 50-60 episodes, it fell well under the 80-100 episode mark needed for syndication in the US. The producer of Harmony Gold, Carl Macek, had a solution: he’d cut three unrelated but similar looking series together into one, called “Robotech.” The shows looked very similar, had similar love triangles, used similar tropes, and even had little references to each other, so the fit was natural. It led to Robotech becoming a weekday afternoon staple with a strong fandom who called themselves “Protoculture Addicts.” There were conventions entirely devoted to Robotech. The supposed shower scene where Minmei was bare-breasted was the barely whispered stuff of pervert legend in pre-internet days. And the tie in novels, written with the entirely western/Harmony Gold conception of the series and which continued the story, were actually surprisingly readable.

The final nail in the coffin of Robotech fandom was the rise of Sailor Moon, Toonami, Dragonball, and yes, Pokemon (like MC Hammer’s role in popularizing hip hop, Pokemon is often written out of its role in creating an audience for the next wave of cartoon imports out of insecurity). Anime popularity in the West can be defined as not a continuing unbroken chain like scifi book fandom is, but as an unrelated series of waves, like multiple ancient ruins buried on top of each other (Robotech was the vanguard of the third wave, as Anime historians reckon); Robotech’s wave was subsumed by the next, which had different priorities and different “core texts.” Pikachu did what the Zentraedi and Invid couldn’t do: they destroyed the SDF-1.

Legion of Super-Heroes

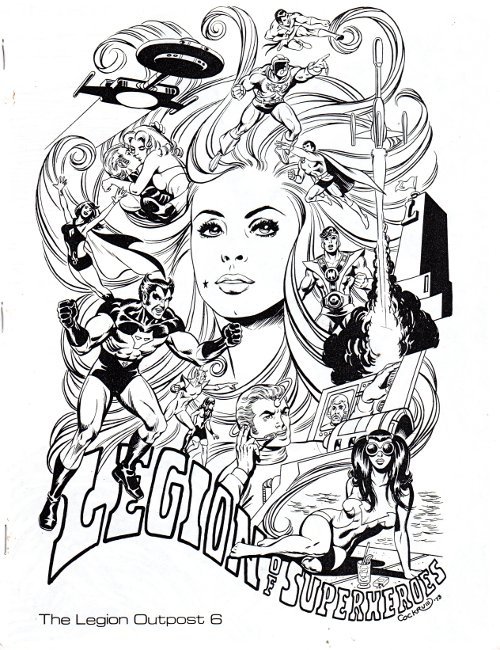

Legion of Superheroes was comic set in the distant future that combined superheroes with space opera, with a visual aesthetic that can best be described as “Star Trek: the Motion Picture, if it was set in a disco.”

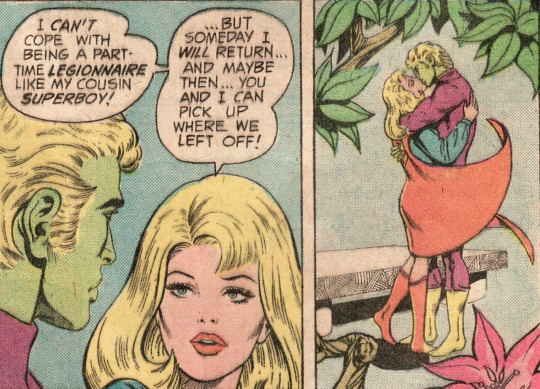

I’ve heard wrestling described as “a soap opera for men.” If that’s the case, then Legion of Super-Heroes was a soap opera for nerds. The book is about attractive 20-somethings who seem to hook up all the time. As a result, it had a large female fanbase, which, I cannot stress enough, is incredibly unusual for this era in comics history. And if you have female fans, you get a lot of shipping and slashfic, and lots of speculation over which of the boy characters in the series is gay. The fanon answer is Element Lad, because he wore magenta-pink and never had a girlfriend. (Can’t argue with bulletproof logic like that.) In other words, it was a 1970s-80s fandom that felt much more “modern” than the more right-brained, bloodless, often anal scifi fandoms that existed around the same time, where letters pages were just nitpicking science errors by model train and elevator enthusiasts.

Legion Headquarters seemed to be a rabbit fuck den built around a supercomputer and Danger Room. Cosmic Boy dressed like Tim Curry in Rocky Horror. There’s one member, Duo Damsel, who can turn into two people, a power that, in the words of Legion writer Jim Shooter, was “useful for weird sex...and not much else.”

LSH was popular because the fans were insanely horny. This is, beyond the shadow of a doubt, the thirstiest fandom of all time. You might think I’m overselling this, but I really think that’s an under-analyzed part of how some kinds of fiction build a devoted fanbase.

For example, a big reason for the success of Mass Effect is that everyone has a favorite girl or boy, and you have the option to romance them. Likewise, everyone who was a fan of Legion remembers having a crush. Sardonic Ultra Boy for some reason was a favorite among gay male nerds (aka the Robert Conrad Effect). Tall, blonde, amazonian telepath Saturn Girl, maybe the first female team leader in comics history, is for the guys with backbone who prefer Veronica over Betty. Shrinking Violet was a cute Audrey Hepburn type. And don’t forget Shadow Lass, who was a blue skinned alien babe with pointed ears and is heavily implied to have an accent (she was Aayla Secura before Aayla Secura was Aayla Secura). Light Lass was commonly believed to be “coded lesbian” because of a short haircut and her relationships with men didn’t work out. The point is, it’s one thing to read about the adventures of a superteam, and it implies a totally different level of mental and emotional involvement to read the adventures of your imaginary girlfriend/boyfriend.

Now, I should point out that of all the fandoms I’ve examined here, LSH was maybe the smallest. Legion was never a top seller, but it was a favorite of the most devoted of fans who kept it alive all through the seventies and eighties with an energy and intensity disproportionate to their actual numbers. My gosh, were LSH fans devoted! Interlac and Legion Outpost were two Legion fanzines that are some of the most famous fanzines in comics history.

If nerd culture fandoms were drugs, Star Wars would be alcohol, Doctor Who would be weed, but Legion of Super-Heroes would be injecting heroin directly into your eyeballs. Maybe it is because the Legionnaires were nerdy, too: they played Dungeons and Dragons in their off time (an escape, no doubt, from their humdrum, mundane lives as galaxy-rescuing superheroes). There were sometimes call outs to Monty Python. Basically, the whole thing had a feel like the dorkily earnest skits or filk-singing at a con. Legion felt like it’s own fan series, guest starring Patton Oswalt and Felicia Day.

It helped that the boundary between fandom and professional was incredibly porous. For instance, pro-artist Dave Cockrum did covers for Legion fanzines. Former Legion APA members Todd and Mary Biernbaum got a chance to actually write Legion, where, with the gusto of former slashfic writers given the keys to canon, their major contribution was a subplot that explicitly made Element Lad gay. Mike Grell, a professional artist who got paid to work on the series, did vaguely porno-ish fan art. Again, it’s hard to tell where the pros started and the fandom ended; the inmates were running the asylum.

Mostly, Legion earned this devotion because it could reward it in a way no other comic could. Because Legion was not a wide market comic but was bought by a core audience, after a point, there were no self-contained one-and-done Legion stories. In fact, there weren’t even really arcs as we know it, which is why Legion always has problems getting reprinted in trade form. Legion was plotted like a daytime soap opera: there were always five different stories going on in every issue, and a comic involved cutting between them. Sure, like daytime soap operas, there’s never a beginning, just endless middles, so it was totally impossible for a newbie to jump on board...but soap operas know what they are doing: long term storytelling rewards a long term reader.

This brings me to today, where Legion is no longer being published by DC. There is no discussion about a movie or TV revival. This is amazing. Comics are a world where the tiniest nerd groups get pandered to: Micronauts, Weirdworld, Seeker 3000, and Rom have had revival series, for pete’s sake. It’s incredible there’s no discussion of a film or TV treatment, either; friggin Cyborg from New Teen Titans is getting a solo movie.

Why did Legion stop being such a big deal? Where did the fandom that supported it dissolve to? One word: X-Men. Legion was incredibly ahead of its time. In the 60s and 70s, there were barely any “fan” comics, since superhero comics were like animation is today: mostly aimed at kids, with a minority of discerning adult/teen fans, and it was success among kids, not fans, that led to something being a top seller (hence, “fan favorites” in the 1970s, as surprising as it is to us today, often did not get a lot of work, like Don MacGregor or Barry Smith). But as newsstands started to push comics out, the fan audience started to get bigger and more important…everyone else started to catch up to the things that made Legion unique: most comics started to have attractive people who paired up into couples and/or love triangles, and featured extremely byzantine long term storytelling. If Legion of Super-Heroes is going to be remembered for anything, it’s for being the smaller scale “John the Baptist” to the phenomenon of X-Men, the ultimate “fan” comic.

The other thing that killed Legion, apart from Marvel’s Merry Mutants, that is, was the r-word: reboots. A reboot only works for some properties, but not others. You reboot something when you want to find something for a mass audience to respond to, like with Zorro, Batman, or Godzilla.

Legion, though, was not a comic for everybody, it was a fanboy/girl comic beloved by a niche who read it for continuing stories and minutiae (and to jack off, and in some cases, jill off). Rebooting a comic like that is a bad idea. You do not reboot something where the main way you engage with the property, the greatest strength, is the accumulated lore and history. Rebooting a property like that means losing the reason people like it, and unless it’s something with a wide audience, you only lose fans and won’t get anything in return for it. So for something like Legion (small fandom obsessed with long form plots and details, but unlike Trek, no name recognition) a reboot is the ultimate Achilles heel that shatters everything, a self-destruct button they kept hitting over and over and over until there was nothing at all left.

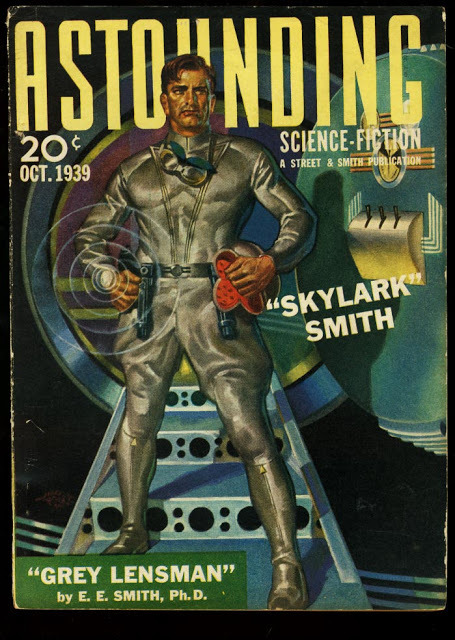

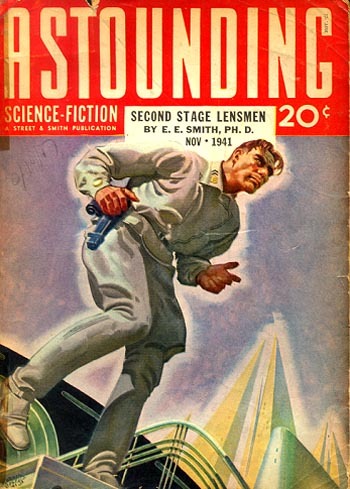

E. E. Smith’s Lensman Novels

The Lensman series is like Gil Evans’s jazz: it’s your grandparents’ favorite thing that you’ve never heard of.

I mean, have you ever wondered exactly what scifi fandom talked about before the rise of the major core texts and cultural objects (Star Trek, Asimov, etc)? Well, it was this. Lensmen was the subject of fanfiction mailed in manilla envelopes during the 30s, 40s, and 50s (some of which are still around). If you’re from Boston, you might recognize that the two biggest and oldest scifi cons there going back to the 1940s, Boskone (Boscon, get it?) and Arisia, are references to the Lensman series. This series not only created space opera as we know it, but contributed two of the biggest visuals in scifi, the interstellar police drawn from different alien species, and space marines in power armor.

My favorite sign of how big this series was and how fans responded to it, was a great wedding held at Worldcon that duplicated Kimball Kinnison and Clarissa’s wedding on Klovia. This is adorable:

The basic story is pure good vs. evil: galactic civilization faces a crime and piracy wave of unprecedented proportions from technologically advanced pirates (the memory of Prohibition, where criminals had superior firearms and faster cars than the cops, was strong by the mid-1930s). A young officer, Kimball Kinnison (who speaks in a Stan Lee esque style of dialogue known as “mid-century American wiseass”), graduates the academy and is granted a Lens, an object from an ancient mystery civilization, who’s true purpose is unknown.

Lensman Kinnison discovers that the “crime wave” is actually a hostile invasion and assault by a totally alien culture that is based on hierarchy, intolerant of failure, and at the highest level, is ruled by horrifying nightmare things that breathe freezing poison gases. Along the way, he picks up allies, like van Buskirk, a variant human space marine from a heavy gravity planet who can do a standing jump of 20 feet in full space armor, Worsel, a telepathic dragon warrior scientist with the technical improvisation skills of MacGyver (who reads like the most sadistically minmaxed munchkinized RPG character of all time), and Nandreck, a psychologist from a Pluto-like planet of selfish cowards.

The scale of the conflict starts small, just skirmishes with pirates, but explodes to near apocalyptic dimensions. This series has space battles with millions of starships emerging from hyperspacial tubes to attack the ultragood Arisians, homeworld of the first intelligent race in the cosmos. By the end of the fourth book, there are mind battles where the reflected and parried mental beams leave hundreds of innocent bystanders dead. In the meantime we get evil Black Lensmen, the Hell Hole in Space, and superweapons like the Negasphere and the Sunbeam, where an entire solar system was turned into a vacuum tube.

It’s not hard to understand why Lensmen faded in importance. While the alien Lensmen had lively psychologies, Lensman Kimball Kinnison was not an interesting person, and that’s a problem when scifi starts to become more about characterization. The Lensman books, with their love of police and their sexism (it is an explicit plot point that the Lens is incompatible with female minds – in canon there are no female Lensmen) led to it being judged harshly by the New Wave writers of the 1960s, who viewed it all as borderline fascist military-scifi establishment hokum, and the reputation of the series never recovered from the spirit of that decade.

Prisoner of Zenda

Prisoner of Zenda is a novel about a roguish con-man who visits a postage-stamp, charmingly picturesque Central European kingdom with storybook castles, where he finds he looks just like the local king and is forced to pose as him in palace intrigues. It’s a swashbuckling story about mistaken identity, swordfighting, and intrigue, one part swashbuckler and one part dark political thriller.

The popularity of this book predates organized fandom as we know it, so I wonder if “fandom” is even the right word to use. All the same, it inspired fanatical dedication from readers. There was such a popular hunger for it that an entire library could be filled with nothing but rip-offs of Prisoner of Zenda. If you have a favorite writer who was active between 1900-1950, I guarantee he probably wrote at least one Prisoner of Zenda rip-off (which is nearly always the least-read book in his oeuvre). The only novel in the 20th Century that inspired more imitators was Sherlock Holmes. Robert Heinlein and Edmond “Planet Smasher” Hamilton wrote scifi updates of Prisoner of Zenda. Doctor Who lifted the plot wholesale for the Tom Baker era episode, “Androids of Tara,” Futurama did this exact plot too, and even Marvel Comics has its own copy of Ruritania, Doctor Doom’s Kingdom of Latveria. Even as late as the 1980s, every kids’ cartoon did a “Prisoner of Zenda” episode, one of the stock plots alongside “everyone gets hit by a shrink ray” and the Christmas Carol episode.

Prisoner of Zenda imitators were so numerous, that they even have their own Library of Congress sub-heading, of “Ruritanian Romance.”

One major reason that Prisoner of Zenda fandom died off is that, between World War I and World War II, there was a brutal lack of sympathy for anything that seemed slightly German, and it seems the incredibly Central European Prisoner of Zenda was a casualty of this. Far and away, the largest immigrant group in the United States through the entire 19th Century were Germans, who were more numerous than Irish or Italians. There were entire cities in the Midwest that were two-thirds German-born or German-descent, who met in Biergartens and German community centers that now no longer exist.

Kurt Vonnegut wrote a lot about how the German-American world he grew up in vanished because of the prejudice of the World Wars, and that disappearance was so extensive that it was retroactive, like someone did a DC comic-style continuity reboot where it all never happened: Germans, despite being the largest immigrant group in US history, are left out of the immigrant story. The “Little Bohemias” and “Little Berlins” that were once everywhere no longer exist. There is no holiday dedicated to people of German ancestry in the US, the way the Irish have St. Patrick’s Day or Italians have Columbus Day (there is Von Steuben’s Day, dedicated to a general who fought with George Washington, but it’s a strictly Midwest thing most people outside the region have never heard of, like Sweetest Day). If you’re reading this and you’re an academic, and you’re not sure what to do your dissertation on, try writing about the German-American immigrant world of the 19th and 20th Centuries, because it’s a criminally under-researched topic.

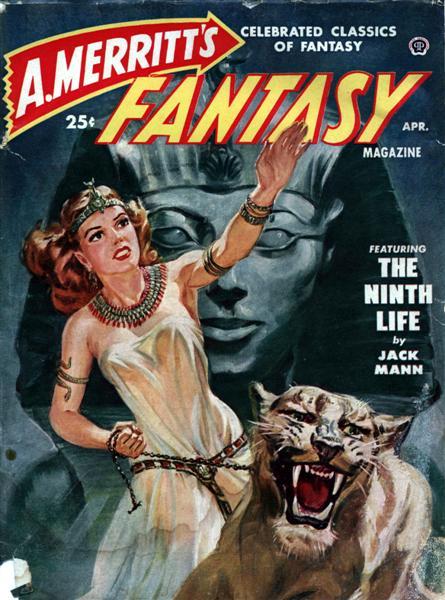

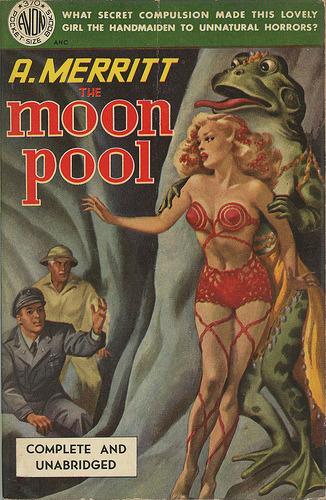

A. Merritt

Pop quiz: who was the most popular and influential fantasy author during the 1930s and 40s?

If you answered Tolkien or Robert E. Howard, you’re wrong - it was actually Abraham Merritt. He was the most popular writer of his age of the kind of fiction he did, and he’s since been mostly forgotten. Gary Gygax, creator of Dungeons and Dragons, has said that A. Merritt was his favorite fantasy and horror novelist.

Why did A. Merritt and his fandom go away, when at one point, he was THE fantasy author? Well, obviously one big answer was the 1960s counterculture, which brought different writers like Tolkien and Lovecraft to the forefront (by modern standards Lovecraft isn’t a fantasy author, but he was produced by the same early century genre-fluid effluvium that produced Merritt and the rest). The other answer is that A. Merritt was so totally a product of the weird occult speculation of his age that it’s hard to even imagine him clicking with audiences in other eras. His work is based on fringe weirdness that appealed to early 20th Century spiritualism and made sense at the time: reincarnation, racial memory, an obsession with lost race stories and the stone age, and weirdness like the 1920s belief that the Polar Arctic is the ancestral home of the Caucasian race. In other words, it’s impossible to explain Merritt without a ton of sentences that start with “well, people in the 1920s thought that...” That’s not a good sign when it comes to his universality.

That’s it for now. Do you have any suggestions on a dead fandom, or do you keep one of these “dead” fandoms alive in your heart?

3K notes

·

View notes

Link

Writer Aamina Khan picked up on the Safe Spaces during Harry’s concerts and Rainbow Direction’s role in creating them since 2014. We are so grateful for this very insightful and sensitive take on your efforts and work and kindly ask you to give the article some well-deserved clicks

When Harry Styles debuted his first single as a solo artist, "Sign of the Times," the general public did a double take. "Harry from One Direction is all grown up," they said. "We didn't expect rock ballads, but he wears it well."

It's true: Harry Styles is a rockstar in his own right. His latest album debuted at number 1 on the Billboard 200 Albums Chart, he sold out his first tour, and he has the crowds of women to match.

But here's what the general public will miss: When Harry steps on stage for his fans, he's the same kid we've grown up with. He's a little taller, a little more fashionable, and a little more rough around the edges. But even all grown up and dressed in head-to-toe Gucci, he's the same endearing kid with the bad jokes (sorry, H). Instead of sexy, he gives fans silly. And those crowds of women? Instead of bras, they litter the stage with their pride flags.

As the world watched Harry grow up, his fans were growing up as well. We were shedding layers of awkwardness and adolescence and embracing strange truths of our own. Over the course of the last seven years, many of Harry's teenage fans began coming to terms with their sexualities and gender identities, and the anonymity of Tumblr made the fandom the perfect place for it.

"Growing up, especially here, you don't hear a lot about LGBTQ+ stuff," said Fer, a 19-year-old fan from Lima, Peru. "When I came out to myself, it was around the time I discovered Tumblr. I don't think I ever heard the word 'bisexual' or knew [of identities beyond] gay or straight until I went on Tumblr. I think it's like that for a lot of people."

We would come home from work and school and post and tweet about One Direction and also about all of our queer little secrets — our crushes, our families, our fears and anxieties. And, in retrospect, it was a little surreal. In front of tens of thousands of strangers, we shed our closets. For a lot of us, myself included, some of the first people we came out to were friends we made from being Directioners.

In 2014, as the band was heading on to tour its third album, Midnight Memories, a group of fans started a project called Rainbow Direction, a queer visibility project encouraging fans to bring pride flags to shows and, most importantly, to be their authentic selves. There were so many of us. Right in front of our eyes, the One Direction fandom went from being an LGBTQ+ friendly corner of the internet to a massive public space where queer girls and femmes belonged. The rainbows weren't a fringe movement — you couldn't ignore the fans and their flags if you tried.

Harry certainly didn't ignore them. He asked fans to pass up their own flags for him to dance with, play with, and tie around himself on stage. When the band played a show the day that marriage equality was passed in the United States, he said, "This place looks very colorful tonight, and for a lot of you I know why, and it's great." To anyone uncomfortable with the flags, Harry was making it very clear very quickly exactly what his feelings were. In 2017, during his first solo world tour, he's featured pride, trans, and bi flags on stage every night without fail, even in Nashville where the venue confiscated all flags in the audience.

But big deal, right? No one should be celebrated just for supporting equality, and we can’t lavish allies with praise for doing the bare minimum. But with Harry, it's more than that: He's created a safe space for queer girls and femmes, for whom mainstream LGBTQ+ safe spaces typically don't exist. With such small actions, he makes us — many of whom are young, closeted, and/or without access to a community — feel seen, comfortable, and protected.

"When I saw Harry at his concert [encouraging us to be] whoever you wanted for that night and running around with pride flags, I felt like I wasn’t in the closet right in that moment," said Riya*, a 20-year-old bisexual Muslim girl. "I was just being myself, even if just for that night."

In Philadelphia, a group of fans passed out hundreds of mini-rainbow flags before the show and told everyone to bring them out for Harry's final song.

"[My friends and I] thought it was cool that someone would do that because some people might have been closeted and not been able to buy one to bring," said Ashley, a 25-year-old bisexual fan who was at the show in Philly. "[Harry] was so surprised. From the audience, you could see him look to his band and just say, 'Wow.'"

Harry has long been known by his fans for refusing to abide by gender norms. He often wore women's blouses and accessorized with nail polish and nonchalance. He breaks the male "black suit" dress code by sporting vibrant florals and full glitter. The picture on his debut album cover is of himself in a pink bubble bath with flowers. He's being real with everyone about who he is, and he’s having fun while doing it.

"I owe a lot of my courage to [Harry's] unwillingness to apologize for who he is," said Ellis, a nonbinary 26-year-old fan. "I think because of him, I felt more confident presenting how I wanted and not taking what people thought so seriously.

"He's gotten so bold over the years, and sometimes, I also think we've helped him because we made it clear that whether he chooses to paint his nails or wear women's clothes, we're not going anywhere. Whenever the media brings up questions about his female fan base, he's always defensive of them and stands up for them. He calls them smart and strong and talks about them with love, and I think a lot of it has to do with the confidence we've inspired in him."

A lot of Harry's queer fans wonder if he's aware of just what he's done for us. Each night he overlooks a dark, crowded auditorium, illuminated only by the light of iPhones, rainbow flags, and sheer queer pride and joy, and we all collectively hope that our gratitude is obvious.

What happens next? You might miss it if you don't know to look. Thousands of hearts swell at once, as a star and his stans share an unspoken understanding that no number of thank you's can be exchanged for what we've given one another. Coming of age, self-discovery, and celebration. And as a perfect close to the moment and the night, the crowd roars at the opening chords of the last song.

*Name changed for privacy.

#rainbow direction#press#rainbow direction press#rd press#harry styles#them.us#Aamina Khan#takemehomefromnarnia#tmhfn#RD

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being Transgender at Goldman Sachs

Michael. DuVally, worked at Goldman Sachs for 15 years, is 58 and twice divorced, with three children. He then appeared at work wearing women’s clothing as Maeve DuVally and informed you about being transgender. Assume some workers respond inappropriately. If you were Maeve’s boss, would you address this issue at a team meeting: (1) Yes, (2) No? Why? What are the ethics underlying your decision?

Goldman Sachs’s trading floors are vast rooms crammed with rows of tightly packed workstations, four monitors for every trader. The two-by-two grids tower over and swallow up their users, so that the only way someone can be identified from across the room is by the decorations affixed to the tops of the screens.

At one desk, a toy vulture peers down, held in place by wire feet. A stuffed eagle in a sports jersey sits atop another monitor. Flags: Brazil, Canada, Norway. A lacrosse stick juts out like a severed head on a pike.

One Wednesday in May, Maeve DuVally walked the rows in a pair of low-heeled black leather pumps, her ankles wobbling slightly. Her pink lipstick popped against her blonde hair, dark jacket and the pearls at her neck. Her eyelashes were full and inky.

Ms. DuVally, a spokeswoman for the bank, passed the flags and the lacrosse stick. She passed the vulture and the eagle. She passed one desk where a little tented card floated at eye level, bearing the Goldman Sachs logo, a rainbow-colored rectangle and the word “Ally.”

She approached the doorway to a senior executive’s office and leaned in. Its occupant, a man in gray dress pants, looked up at her quizzically.

“Hello,” she said, and waited.

“Maeve DuVally,” she said, after a moment.

“Hello,” the man said, blinking.

“Michael DuVally,” Ms. DuVally said. “I’ve changed genders.”

“I did not recognize you!” the man said.

Ms. DuVally explained that she had not yet gotten around to telling all of her colleagues of her decision to come out as transgender. She told a story: One person she had shared the news with was a fellow member of a Goldman working group; he had replied, “Great — now we have another woman on the committee.” Ms. DuVally and the man in the office laughed at that. Then she said goodbye, and that she was looking forward to seeing him again at a meeting later that day. The man said softly, “New experiences for all of us.”

Wall Street wakes up (a bit)

Wall Street has had a hard time kicking its reputation as a dismal place for people who aren’t straight white men. Gone — mostly — are the days when investment banks would pick up strip-club tabs and female employees were harassed as a matter of course. It may be harder now to find a trader nicknamed “Porno Ray” (he worked at Bear Stearns), and the Volcker Rule has taken the swagger out of the guys who used to walk away from a day’s work with enough cash to buy a new Lamborghini — or acted like it, anyway. Despite these advances, a fleece-vested bro culture remains, and there are still plenty of obstacles to success for minorities and women.’

The group photo of Goldman’s 2010 managing director class, for example, is a sea of men with a sprinkling of women at the front. Ms. DuVally was in that class; she keeps the photo, in which her face appears above a suit and tie, on her desk. When she arrived for work as Maeve on the Tuesday after Memorial Day, only the second employee to use official channels to manage her transition at Goldman, she was testing just how tolerant and accepting a big American bank could be.

Goldman presents itself as being ahead of the curve on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender issues. It has offered health and relocation benefits to same-sex couples since 2000. It expanded its employee medical plan to cover gender reassignment surgery and hormone therapy in 2007, years ahead of JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup. This year, Goldman’s former chief executive, Lloyd Blankfein, received the Ally Award from the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center, a 35-year-old institution that supports the L.G.B.T. community in New York City.

Employees can choose to display posters and cards in their work areas that identify them as allies dedicated to “encouraging the use of inclusive language” and “mentoring and being a resource for L.G.B.T. people.” A giant rainbow pride flag is affixed to a window high above the equities trading desk, beside the office of R. Martin Chavez, the co-head of Goldman’s securities division and the firm’s most senior openly gay executive.

Goldman still has problems. On June 5, William Littleton, a former vice president who is gay, sued the bank for discrimination. He said his direct supervisors had failed to act when other bank employees undermined him, including when one colleague explained that he had been kept off a conference call because he sounded “too gay.” One supervisor, he said, had belittled him with comments like, “You look so Miami today.”’

There is one other Goldman employee who has formally transitioned at work (that is, involved the human resources department, changed names, made an announcement and so on): Katie Krasky, an associate on Goldman’s regulatory policy team. She was hired in February 2017, told her bosses that June of her intention to transition, and debuted her new name and pronouns that October.

Ms. Krasky said in an interview that she had not known she was a pathbreaker. She assumed there must have been other employees like her. “While I wasn’t able to find or connect with anyone who identified as transgender during that process, I felt it was probably foolish to assume I was the first, just because of the math,” she said. “It didn’t seem like it was very likely.”

A 2017 study published in the American Journal of Public Health estimated that 0.39 percent of adults in the United States are transgender. If that proportion were applied to Goldman’s ranks, there would be as many as 140 transgender employees among the bank’s 36,000.

Goldman’s head of human resources, Dane Holmes, said Ms. DuVally and Ms. Krasky weren’t the only two transgender employees at Goldman, they’re just the only ones who have formally transitioned while at work. “There’s a lot of fluidity around how you think about sexual identity,” Mr. Holmes said. “We’ve had people who came into the firm at some different stages of their transition.”

One employee, Mr. Holmes said, had a name that befitted both a man and a woman, so she simply transitioned without any official announcement. “There are certainly people who work here who are transgender who have chosen not to self-ID,” he said. He declined to say exactly how many.

‘I never, on a conscious level, thought that there was anything I could do’

In the Goldman Sachs communications department, Ms. DuVally and her colleagues are concerned to an extreme with the stories they tell, and with what they are and are not allowed to say. Recently, while visiting the bank, I made an idle comment about Goldman’s relaxed new dress code. Ms. DuVally replied, “You can’t put this in your story, but my assistant wears jeans every day now.” Another co-worker, who has worked with Ms. DuVally for years, told me he had never seen her happier. A few hours later, he emailed to say he could not be quoted saying that.

Ms. DuVally, who has worked at Goldman for 15 years, is 58 and twice divorced, with three children. In an interview, she said that she had been unhappy for most of her life. “I drank too much in the past, and I was extremely self-critical,” she said. “In retrospect, I can say now I didn’t like the fact that I was a male.”

Before she started dressing in women’s clothing, she said, she could not remember looking at herself in the mirror and feeling anything other than disgust. “I believe from a very early age I’ve wanted to be a woman,” she said. Somehow, she added, the sense was both vague and strong. “I did not like anything that was masculine about me. But I never, on a conscious level, thought that there was anything I could do about that.”

Last year, Ms. DuVally said, she discovered that she liked wearing women’s clothing. She did so on weeknights, at her apartment on the Upper East Side. She found a support group for transgender people and made new friends.

At first, the thought of expressing herself in this way at Goldman did not cross her mind. But then, beginning late last year, she occasionally wore light makeup to work. Sometimes she would appear before her colleagues wearing bright red or pink lipstick. A few nights before Thanksgiving, she wore makeup along with a tuxedo to a black-tie event, where she mingled with other bank employees and journalists.

Ms. DuVally saw herself as living two lives throughout the fall and winter. One, where her new friends knew her as Maeve, was exciting and filled with a happiness she had never before experienced. The second, her life at work, where she had to keep being Michael, was grinding away at her.

In December, on the mornings she went to work from yoga class, she began showing up in flowy yoga pants and boots with heels. She would ride the two elevators it took to get to her office on the 29th floor and then change into a suit. The form of Michael felt stifling. Sometimes she couldn’t even last the whole day downtown in the unnatural feeling of her men’s clothing. She’d get dressed in women’s clothes and makeup while still at work, in preparation to leave at the end of the day.

Then, in March, an invitation went out to the bank’s employees: Goldman’s L.G.B.T. network was hosting a panel on “how to be stronger allies to the transgender and gender non-conforming community.” Ms. DuVally showed up to the event, in Goldman’s auditorium, in a wig and makeup, and afterward she introduced herself to some bank employees.

Ms. DuVally found the event encouraging. One co-worker, who watched it remotely from London, took copious notes and emailed them to the communications group afterward. Everyone who attended received laminated cards explaining correct pronoun usage. Ms. DuVally realized, she said, that it was time to come out as transgender at Goldman.

The bank is a place of rigid protocols, and she knew her debut as Maeve would require weeks of preparation. After Ms. DuVally informed her bosses of her decision, a human resources specialist was assigned to handle her case. Ms. DuVally got new business cards, a new ID badge, a new email address. She got a new profile in Goldman’s internal directory, so that when she joined work discussions digitally, the meeting software would display to all participants her smiling, feminine face.

A co-worker of Ms. DuVally’s in London used her access to the bank’s employee website to change Ms. DuVally’s name in past internal articles from Michael to Maeve. The bank’s security team let her into their offices to have her new-look photograph taken at a time when no one she knew and hadn’t told about her transition would chance upon her.

Ms. DuVally and her colleagues in the communications department knew her decision would be of interest to journalists, and they discussed how to keep it a secret until the last minute. In mid-May, Ms. DuVally attended a happy hour Goldman hosted for reporters at a bar overlooking New York Harbor. She was still calling herself Michael, still dressed as a man. Tucked into her jacket, out of sight for most of the evening, was a large, bubblegum-pink wallet. I noticed it when she took it out at the bar, and Ms. DuVally hurried me away from the group. Only out of earshot, and after stipulating that it was a secret, did she explain why.

In the corporate sphere, Ms. DuVally imagined that her transition would be a binary thing — that a switch would be flipped. But word was getting out. People outside her immediate circle learned of her transition plan. On May 22, when I interviewed Asahi Pompey, Goldman’s global head of corporate engagement, she gushed about the name “Maeve.” Later that day, when I told Ms. DuVally, she was surprised Ms. Pompey was aware of it.

LONG ARTICLE CONTINUES ...

0 notes